I have a cloud of sadness within me as I speak. It has to do with an absence, a non-event which, both as a product in itself and as the product’s fate, could easily stand – among similar testimonies – as symbolic of the mission of this gathering, and a number of others like it, at least in all societies which value the exertion of the mind and products of the imagination.

Before I state what that non-event is, I wish to emphasize very strongly that this is not meant as an indictment of this Book Fair of which I consider myself a part, having been with it – albeit marginally – from its very inception. That would be grossly misleading. My remarks represent a personal wish, generated by the nation’s current crisis of existence, and extend beyond this present location and time, even though they do take off from there. They are a continuation of a discourse on which I embarked years ago – and formed part of my BBC Reith Lecture series – CLIMATE OF FEAR. That discourse was nudged awake quite fortuitously when I visited the London Book Fair three to four weeks ago, where the issue of censorship resurfaced. In any case, this absence I speak of, paradoxically, constitutes an integral part of the story of the Book, narrating the predicament of much of humanity in scattered parts of the world – and on so many levels, both specific and general.

For us in this nation, that predicament is hideously current and specific. We are undergoing an affliction that many could not have imagined possible perhaps up to a decade ago. In a way, both that product, and its absence are simultaneously instruction and consolation. On the one hand it brings home to us the price that others have paid – and still pay – for complacency, timidity, evasion, and/or failure to grasp the nature, and multiple guises of the Power drive. The obsession to dictate, dominate, and subjugate. On the other hand, it consoles us, in that painfully ironic way, that others have been there before, and many more are yet lined up to undergo – if I may utilize an apt seasonal metaphor, this being the Easter season – many more unsuspecting nations and communities, currently insulated from a near incurable scourge, are lined up to undergo the same Calvary.

To the product then: It’s just a book, but then, more than ‘just a book’ – written by Professor Karima Bennoune, an Algerian presently teaching at Berkeley University, California. And the title? YOUR FATWA DOES NOT APPLY HERE. It is not a work of fiction. It is a compilation – with commentary and analysis of course – of experiences of individuals – men, women, young, old, professionals, academics, entire families and others – among them her own father. It is a record of unbelievable courage and defiance, yes, also of timorousness and surrender, of self-sacrifice and betrayals, of arrogance and restraint, intelligence and stupidity, fanaticism and tolerance – in short, a document of Truth at its most forthright and near unbearable, the eternal narrative of humanity that illustrates, the axial relation between the twin polarities called Power and Freedom which, I persist in pointing out, stand out as the most common denominator of human history.

I feel sad that through this absence, Africa north of the Sahara could not meet and speak to Africa South on Nigerian soil, console and instruct us through a shared experience, one from whose darkness one nation recently emerged and into which the other is being dragged by the sheer deadweight of human mindlessness. It is such an important book, one that has a sobering relevance – does one have to reiterate? – for this nation. It is not quite over yet for Algeria by the way. Only yesterday I read in the papers that eleven soldiers were ambushed and killed by forces of identical mental conditioning to the ones that are currently traumatizing this nation. We can only hope that Karima Bennoune does not have to drastically update her account through a resurgence of a traumatic past. So much on the product itself.

Now comes the question: what would have been the effect of that title on most of us, seeing it displayed in one of the bookstalls of a participating publisher? Let’s begin from there. Even before we have opened the cover, what impact does it have on us, the local consumers? This is not a rhetorical question – what is it in the title itself that guarantees in advance that the average viewer would instinctively approach it with some trepidation? This is a familiar battle ground for thousands of affected writers, and constitutes the phenomenon that I wish to drag into this specific context, seeing that the book is available through all the normal sales channels elsewhere, and has been reviewed extensively in numerous media. It leads inevitably to the question: have we been shortchanged, albeit through circumstances too convoluted to go into here – in an environment to which such a history is excruciatingly pertinent?

One should not cry over spilt milk, yet one should never let an opportunity go to waste to recoup one’s losses wherever possible – even in divergent directions. In this case, as I hinted earlier, the very absence forms part of our literary mission. I consider this work of such relevance that I am persuaded that it should be made compulsive reading for everyone in leadership position in this nation, beginning from the President all the way down to local councilors, irrespective of religion, and community leaders. I intend to adopt Professor Bennoune’s book as entry point into the interrogatories for the very contestation that is summed up in the title of this address – “The Republic of the Mind and the Thralldom of Fear”. I intend to pose questions such as: should such a work constitute a contentious issue in the first place? Is our world now in a condition where a work that may – repeat – may – explore and narrate unpleasant histories is approached as an instant minefield for its handlers? Is any interest group, as long as it is sufficiently vociferous, reckless and dangerous, entitled to bestride and menace our world once such a minority decrees even factual history unpalatable or unflattering? Do we now instinctively make assumptions of negative responses on behalf of such a minority? Does anyone possess a right of imposition in the first place? What does that mean for any community?

I pose these questions because my increasing conviction is that our space of volition and equality of choice is rapidly collapsing under internal relationships based on fear and domination, on dictation and imposition. This is not the view of this speaker alone. Both Egypt and Tunisia, one after the other, are solid proofs that this shrinkage of space is an obsessive project by the assiduous cultivators of the realm of thralldom, and we have seen how it is answered in both instances. My business here is not to urge the adoption of the solutions pursued in either nation, or indeed Somalia, but to point out an existing agenda of control, manifested in different ways and degrees, and consequently drawing unpredictable responses.

But quickly, that question, are the people themselves sometimes collaborators in the shrinkage of that space of choice, that space of freedom? This, indeed, was the disquieting issue that triggered off the London discussion, catapulting the Nigerian predicament to the fore. We must be honest in our answers. When we look into the demands and impositions by one section of society upon another, coldly and analytically, we find that, very often, our instinctive assumptions are totally divergent from the actuality of relationships between such groups. We find that we have conceded what was never at issue, or else can be argued and clarified through mutual exchange. We find that sensitivities are often exaggerated, or else unnecessarily indulged. It is a lazy intellectual habit, one that is born of a timorous attitude for frank and honest dialogue. Mutual respect is built by clarification, not by avoidance or unjustifiable concessions, which is an attitude of condescension, a patronizing approach that is not only disrespectful but unhealthy.

To begin with our immediate community here in Nigeria as testing ground, let us consider the ‘People versus Boko Haram.’ Boko Haram represents the ultimate fatwa, of our time. It has placed a fatwa on our very raison d’etre, the mission, and justification of our productive existence. I do not think that this claim is in contention. The next question is: does the Boko Haram fatwa remotely represent the articulated position of the majority of moslems in this nation? My reading over the past few years is an unambiguous NO! Again and again the declaration that those words represent in Bennoune’s title is the very manifesto with which the nation has been inundated by moslem intellectuals, politicians, community leaders quite openly in their pronouncements on Boko Haram. ‘They are not true moslems’ has become the persistent mantra from North East to West, all the way southwards across the Niger. Grasping the nearest such declaration to hand, only two days old, the governor of Osun state, a moslem, declared in categorical terms:

“A visibly angry Osun State Governor called on Moslems to rise against atrocities perpetrated by the fundamentalist group in the name of religion”. In his own words,

We must protest seriously against the sycophants who hide under religion to perpetrate evils in our land; it must be done nationwide. We reject everything that Boko Haram represents. Our religion rejects everything these evil characters project in the name of islam. We must not be silent, because Boko Harm represents evil.”

Now what does that mean, this exhortation that has been echoed by Emirs, islamic scholars, islamic councils, politicians and lawgivers etc. The least that the intimately connected people of the book – publishers, teachers, thinkers of all faiths can contribute, is to exploit opportunities such as this market of ideas – to spread the word in all possible forms, most especially where an example is provided through the histories of those who failed to rally the mind when encroachment on the space of ideas was still in infancy. What these voices now proclaim, somewhat belatedly, is simply that the edicts of Boko Haram – in short, its fatwa’s –are worthless and unacceptable to the rest of society. Bennoune’s book, the string of words that makes up the title, is the charter of rejection that the Algerians, as a people, flung at the murderous fundamentalists as they battled for over ten years for their freedom. It represents a collective challenge for the rest of us: to go beyond even the contents of the work and actualize its lessons in our lives. To do less is to concede that the will of Boko Haram is the will of all humanity.

Why else are we gathered here? Boko Haram anathemizes books, destroys books and destroys their institutions, but we are here, in a surrounding of, and celebration of books. Yes, indeed, a Book Fair is itself a statement of rejection of Boko Harm’s fatwa. It is an implicit yet overt gesture of contempt for the delusions of grandeur of that movement and its homicidal avocation. But then, a Book Fair owes itself the full complement of what renders it – itself . Its mission, as an instrument of enlightenment, must not be compromised by the diktat – implicit or overt – of whatever makes no disguise of its contrary mission and manifests itself as an enemy of enlightenment.

An army that remains in the barracks even when assailed by enemy forces is clearly no army at all, but a sitting duck. We cannot recommend that we all sign up and join the uniformed corps as they make their rescue sorties into caves and swamps in the forest, not only to destroy the enemy but now, primarily, to rescue our children who were violently abducted from their learning institutions to become – let’s not beat about the bush, let us face the ultimate horror that confronts us, so we know the evil that hangs over us as a people – to become sex slaves of any unwashed dog. Those children will need massive help whenever they are returned to their homes. To remain in denial at this moment is to betray our own offspring and to consolidate the ongoing crimes against our humanity. There is no alternative: we must take the battle to the enemy. And this is no idle rhetoric – the battlefield stretches beyond the physical terrain. We are engaged in the battle for the mind – which is where it all begins, and where it will eventually be concluded. And that battlefield is not simply one of imagination, it is one of memory and history – our histories, what we were, and a consciousness of the histories of others – what happened to them in the past, how they responded, and with what results.

My dear colleagues, there may be hundreds of soldiers out in the forests of Borno, Adamawa, Yobe, but this battle is very much our own., primarily ours, and we should display as much courage as those who are dying in defence of what we value most, as writers, and consumers of literature. At least I like to believe so, to believe that nothing quite comes quite that close to our self-fulfillment as the liberation of the mind wherever the mind is threatened with closure. This is what is at stake. At the core of this affliction, it is this that is central to the predicament of our school pupils wondering through dangerous forests at this moment through no crime that they have committed. We sent them to school. We must bring them back to school.

Why did this nation move out of its borders to join other West African nations to stop the maniacs whose boastful agenda is to cut a bloody swathe through communities of learning, of tolerance and peaceful cohabitation? What does a united world say to the agents of heartbreak and dismay when religion powered mayhem is unleashed against innocent workers gathered at prime time in a motor park to resume their foraging for daily livelihood? It has happened before – let us not forget that, by the way! What, in short, do Book Fairs say as we learn of the steady, remorseless assault on the seminal places of culture, ancient spiritualities and book learning. We have not so soon forgotten the destruction of the monumental statues of Buddha, the historic monuments and tombs of Timbuktoo, her ancient manuscripts – repositories of islamic scholarship that pre-date the masterpieces of Europe’s medieval age? The true moslems, the authentic strain of the descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, pride themselves as people of the book, hence those lovingly preserved manuscripts of Timbuktoo, treasured and tended through generations of moslems. In such circumstances, whose side do we take, when children are blown up and slaughtered in their school dormitories, their teachers and parents hunted down for daring to disobey that phillistinic fatwa that forbids learning? Do we remain in our barracks? And I am not speaking of military barracks!

For it has not just begun, you know. We are speaking of the prosecution of a war that, four years ago already, was already galloping to its present blatant intensity. That it has attained the present staggering figures that numb our humanity with the abduction of female pupils to serve as beasts of burden for the enemy, does not disguise past failures, self-inculpating silences, and even tacit collaboration in places. Try as we might, we cannot insulate ourselves from the horrors to which our children are daily exposed through a fear to undergo, even for our own instruction, the vicarious anguish of others. First, it is futile, the ill wind currently rattling our windows will shortly blow down the flimsy structures we erect around our heads. Symbolism is all very well and – yes indeed – no one should underestimate the value of this symbolic enclave whose mandate we shall be acting out over the next seven days. The palpable products – albeit of words only – that emerge from within this symbol however is what constitutes the durable product, reinforcing morale and conveying to the maimed, the traumatized, the widowed and the orphaned, the suddenly impoverished, displaced, the bereaved and other categories of victims a sliver of reassurance that they are not abandoned.

And why should they feel abandoned in the first place? Why not indeed? Permit me to impose on the leadership of this nation a simple, straightforward exercise in empathy. I want you to imagine yourself in a hospital ward, one among many of the over a thousand victims of the latest carnage in Nyanya – do remember that the actual dead and wounded are not the only casualties – I could refer you to JP Clark’s Casualties for a penetrating expression of the reality of the walking wounded – however, let us take it step by step, let us retain within the territory of physical casualties – imagine that you are one of them, on that hospital bed. You find yourself in the role of playing host to the high and mighty. You are immobilized, speechless, incapable of motion except perhaps through your eyelids. The guests stream in one by one, faces swathed in concern – local government councillors, ministers, legislators, governors, prelates, all the way up the very pinnacle of power – the nation’s president. They even make promises – free medical treatment, habilitation, etc etc. They take their leave. Your spirits are uplifted, you no longer feel depressed and alone.

Considerately mounted eye level on the opposite wall is a television set, turned on to take your mind off your traumatized state and provide some escape for the mind in your otherwise deactivated condition. A few hours after the departure of your august visitors, you open your eyes and there, beamed live, are your erstwhile visitors participating in chieftaincy jollifications a few hundred miles away, red-hot from your sick-bed. A few hours later, the same leadership is at a campaign rally, where the chief custodian of a people’s welfare is complaining publicly about an ‘inside job’ – that is, someone had allegedly diverted his campaign funds to unauthorized use. That national leader then rounds up his outing with a virtuoso set of dance steps that would put Michael Jackson to shame.

That is all I ask of you: to undertake a simple exercise in human empathy, asking the question – as that victim, what would you think? How would you feel? That is all. Would you, playing back in your mind the reel of that august visitation, would you feel perhaps that the visit itself was all a sham, that those sorrowing visitors were merely posing for political photo shots, that the faces were studiously composed, their impatient minds already on their next engagement on the political dance floor? Or would you feel that this was a time that a nation, led by her president, should be in sackcloth and ashes – figuratively speaking of course? That there is something called a sense of timing, of a decent gap between the enormity of a people’s anguish and ‘business as usual’? And do let us bear in mind that that dismal day in Nyanya went beyond a harvest of body parts, of which yours could very easily have been part, there was also the dilemma of two hundred school children, some of whom could very easily have been your own – vanishing under violent conditions. Would you think that perhaps, in place of the dance floor, a national leader should have been holding round-the-clock emergency meetings on the recovery of those girl children, mobilizing the ENTIRE nation – and by entire, I mean, entire, including the encouragement of volunteers, for back-up duties to the military, demonstrating the complete rout of the prolonged season of denial, the total transformation of leadership mentality in the nature of responses to abnormalities that are never absent, even in the most developed societies.

If anyone requires contrasting models of simple, commonsense responses – not even the responses of experts, just leadership – then look towards South Korea. That tragic ferry disaster that overcame schoolchildren on an outing was not even a case of deliberate, criminal assault on our humanity. It was a human failing, probably of culpable negligence, but not part of a deliberate act of human destabilization. It was a frontal, in-your-face assault. Study the nature of leadership response in that nation! Today’s media carry headline banners that nearly two hundred children remain missing. Even if it were twenty, ten, one, is this the time for dancing? Or for silent grieving? What is the urgency of a re-election campaign that could not be postponed in such circumstances? Will the yardstick of eligibility for public office be the ability to dance to Sunny Ade or Dan Marya? The entire world regards us with eyes brimful with tears; we however look in the mirror and break into a dance routine. What has this thing, this blotched, mottled space become anyway? It is a marvel that some still wave a green-white-green rag called a flag and belt out one of the most unimaginative tunes that aspires to call itself a nation anthem. It has become a dirge – that is what it is – a dirge, and what we call a flag is the shroud that now hovers over a people that are even incapable of the dignity of self-examination, self-indictment, and remorse, which would then be a prelude to self-correction and self-restitution, if leadership were indeed attuned to the responsibilities of leadership.

To sum up, one would rationally expect that the leadership mind, belatedly applied to cautionary histories such as YOUR FATWA DOES NOT APPLY HERE, will courageously attune itself to an altered imperative that now reads: YOUR FATWA WILL NOT APPLY HERE. This would be manifested in a clear response to the enormity of the task in which the nation is embroiled. Not all national leaders can be Fujimori of Peru who personally directed his security forces during a crisis of hostage-taking – no one demands bravura acts of presidents. However, any aspiring leader cannot be anything less than a rallying point for public morale in times of crisis and example for extraordinary exertion. Speaking personally now, my mind goes to the lead role played by President Jonathan in this nation in the erstwhile campaign to ‘BRING BACK THE BOOK’ an event at which we both read to hundreds of children. So where are the successors to those children? The reality stares us in the face: Among the walking wounded. Among the walking dead. In crude holdings of fear and terror. Today, we shall not even be so demanding as to resurrect the slogan BRING BACK THE BOOK – leave that to us. It will be quite sufficient to see a demonstrable dedication that answers the agonizing cry of: BRING BACK THE PUPILS!

Emperor Nero only fiddled while Rome burned. There is no record of him dancing to his own tune. There is, nonetheless, an expression for that kind of dance – it is known asdanse macabre, and we all know what that portends.

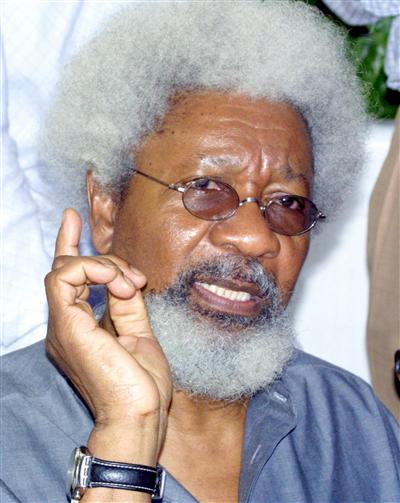

Wole SOYINKA