By EDWARD A. GARGAN, Special to the New York Times

Published: February 21, 1986

KANO, Nigeria— In a room next to the open-air student mosque at Bayero University, Abubakar Imam Ali-Agan nudged his red felt cap up off his forehead. A Koran, the edges of its pages blackened from use, lay on the table before him.

”We ought to be a Moslem state,” he declared.

”Inshallah,” murmured the two dozen students crowding around Mr. Ali-Agan. ”God willing.”

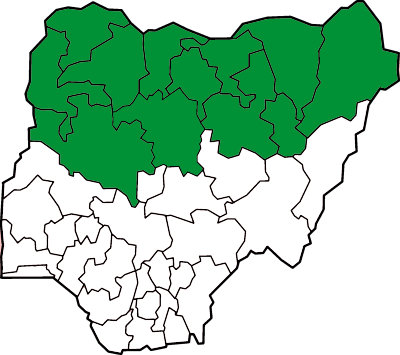

Here in the northern heartland of Nigeria, agitated demands for the gradual Islamization of the country are impassioned and growing louder. Calls to impose Islamic sharia courts in the largely Christian and animist south have been increasing. And the same voices are urging the Government to accept membership in the Islamic Conference Organization, a 45-member group of predominantly Islamic countries.

Islam binds this section of the country together, crossing ethnic and linguistic boundaries, defining the soul of the north. But across the south, from the eastern Ibo to the preserve of the Yorubas around Lagos, Islam is seen as a shadow spilling across Nigeria’s shaky secularism. ‘Potential to Destabilize’

”This really does have the potential to destabilize the country,” said a banker here who is to move to Lagos soon. ”I think it is fair to say there is tension. It has always been there, but it’s been on a more subdued level. It’s always been there, but it’s never been the real issue it is now in Nigeria.”

Most experts on Nigeria agree that Moslems constitute close to half of the total population of more than 80 million and that Christians make up roughly one third. Most of the rest are animists. The experts acknowledge that census information is not reliable and is out of date.

In Lagos, anxiety over the burst of Islamic fervor is acute. ”It’s a dangerous, explosive trend,” said Dele Giwa, editor of the influential weekly magazine News Watch. ”In the worst case, I see a situation where die-hard Christians and die-hard Moslems are fighting in the streets.”

For more than a month, northern religious leaders and traditional rulers, editorial writers and students have been campaigning for the establishment of sharia courts – religious courts for settling disputes between Moslems according to the dictates of the Koran – in the country’s south.

Already, sharia courts in the north hear some civil and domestic matters. Criminal cases remain the province of government courts. ‘Part and Parcel of Our Life’

”Sharia is part and parcel of our life,” said Mr. Ali-Agan, who is the secretary of the Moslem Students of Nigeria at Bayero University. ”If you tell me there is no sharia, then I have no right to live here. If you are telling me sharia has no right to come to Nigeria, I cannot live in Nigeria as a Moslem.”

When Arab traders first started journeying by camel across the Sahara, one of the desert’s tracks ended in what is now Kano. With them, the traders brought architectural styles and a flare for commerce. They also brought Islam.

Today the small modern portion of the city is jigsawed by sweeping boulevards intersecting in huge ”roundabouts” echoing British colonial road design. Vespa drivers, the sleeves of their white robes billowing in the wind, dart between battered taxicabs. City workers in long pink cotton shirts sweep the gutters.

But it is behind 10-foot-high ocher-colored mud walls that the old city lies, the center of Kano life. Inside the old city, the ancient Kano market is still the scene of trading, a place where craftsmen embroider the multicolored pillbox hats, or fula, typical of this area, where money-changers squatting on mats will accept Swiss francs, Japanese yen or Canadian dollars, where metal workers under low mud arcades hammer silver stirrups and bridles. The Call to Prayer

Every day at 1 P.M., the call of the muezzin summoning Moslems to prayer strains faintly from the mosques scattered about. Trading slows. Women with jugs of water balanced on their heads trundle through the alleys that channel among the shops.

Plastic prayer mats, made at a factory in town owned by an Indian, are rolled out in darkened shops, next to piles of vegetables. In narrow side streets, thousands of faithful turn eastward and touch their foreheads to the ground.

”If you are looking for a perfect typical Hausa city, a Moslem city, it’s Kano,” said Abba Dabo, the managing director of The Triumph, the only daily newspaper published here. ”Here is a more traditional town, an older town.”

There is a widespread feeling here that the south has somehow sprinted ahead of the north in education, business and industry, that the south has made greater strides in escaping the restraints of tradition and that it is, as a consequence, unfairly prospering.

”Historically, the Hausa have not embraced Western education,” Mr. Dabo said, referring to the ethnic group that dominates the north. ”Even here, so many people have come from villages to urban areas. They see that the reality is you have to speak English to get decent work. You have to have your education to get a job. They come from their villages and hate it. There was a tendency not to follow the rest of the country.”

Despite this, nearly all of Nigeria’s leaders have come from the north, and nearly all have been Moslems. Under the Government of the previous President, Maj. Gen. Mohammed Buhari, many Christian schools were taken over by the state, and permits to build churches were held up while the construction of mosques was stepped up. Nonetheless, Mr. Dabo said, there is still a sense of insecurity and inadequacy here.

”We are, as they say in Hausa, holding the horns and they are milking the cow,” Mr. Dabo said. ”What do we have for ruling this country for so many years? Nothing. We are educationally and economically backward. That is why we are politically volatile. If there is going to be a revolution it is going to start here.”

At the university, Mr. Dabo’s analysis of northern politics and society is ignored. What matters is religious conviction.

”We need Islam in the pure form,” said Mustapha Isa Qasim, the president of the Moslem student group. ”The debate is on. It doesn’t mean we are preparing for war. We are not. But we are up to the task of an intellectual fight.” Challenge to Christians

But more revealing is a challenge the student group issued to the Christian Association of Nigeria, which denounced both the proposal to introduce sharia law in the south and Nigeria’s flirting with the Islamic Conference.

”We particularly wish to warn the Christians,” a leaflet posted around campus read, ”to desist from making further comments on the so-called move to make Nigeria a member of the Islamic Conference Organization. We warn our Christian compatriots not to force us into breaking our unilateral declaration of peace. They should not deceive themselves that the Moslems’ silence in this country means helplessness or cowardice. We are ever ready for any eventuality.”

The banker said the polarization of the country along religious lines would inevitably affect the country’s political future, especially if the promise of a return to some form of civilian rule by 1990 is kept.

”It will probably become a classic religious battle,” he said. ”It will affect party formation. I wouldn’t be surprised to see parties assigned to a particular religion.”

In the south, where many newspapers are based, cartoonists and editorial writers have reacted ferociously to the challenge. A recent cartoon in a newspaper showed a bearded imam jiggling prayer beads in his left hand while stamping on a copy of the Constitution. Under the country’s suspended Constitution of 1979, Nigeria is constituted as a secular state. ‘An Ill Wind’

Under a headline ”An Ill Wind,” The Daily Star of Enugu, said in an editorial, ”In a nation as diverse as Nigeria, it is not in the interests of its people to have an official religion, nor can one religion be imposed on the whole people.”

In a similar vein, the newspaper The Punch wrote, ”Given our recent tragic experiences as a nation and given Nigeria’s sensitivity to religious issues, we believe that any attempt to introduce religious factors into the business of government, no matter the altruistic purpose and no matter the genuine reason – such a step is to all intents and purposes similar to sounding a drumbeat for crisis.”

The Government’s response to the harshness of the verbal clashes has been relatively muted. After weeks of conflicting statements by members of his Government – some insisting that Nigeria was a member of the Islamic Conference Organization, others denying it – the President, Maj. Gen. Ibrahim Babangida, announced that the country had in fact joined the group.

At the same time, however, he appointed a 20-member presidential committee to examine the implications of membership for Nigeria and its secular status.

No Government that is national and anxious to succeed will deliberately create problems for itself, General Babangida said, in notifying the nation that it had joined the Islamic group. Decision Is Defended

He defended the decision by describing the organization as a forum for technical, economic and cultural cooperation among member countries. Nonetheless, he appeared to leave room for a revocation of the decision if the committee determines that membership in the group will worsen religious tensions in the country.

As for the introduction of sharia courts in the south, no senior Government official has publicly said a word.

”The Government is very, very slow in coming out,” the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Lagos, Anthony O. Okogie, said. ”It is categorically stated in the Constitution that Nigeria is a secular state. To ally Nigeria with a religious organization is wrong. Nigeria is not an Islamic state. If we allow this, it means Nigeria has no Constitution.”

The Archbishop, in a snow-white cassock, sat shoeless behind his desk waving a ruler for emphasis. ”If the Government isn’t careful, there may be some trouble,” he said. ”I don’t think there will be violence. The possibility is there. But as level-headed men, we must search for peace.”

But some commentators on Nigeria, even those with acknowledged biases, say it will not be easy to soften the rapidly hardening edges of religious hostility and intolerance.

”Pressure is being put on the country to Islamicize,” Mr. Giwa, the editor, said. ”It’s becoming a big national crisis.”

Leave a Reply