Last week two American aid workers who had contracted Ebola while working in west Africa were released from a US hospital and pronounced “recovered”. They had been flown to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, from Liberia earlier this month to receive care in the hospital’s specialized infectious disease unit.

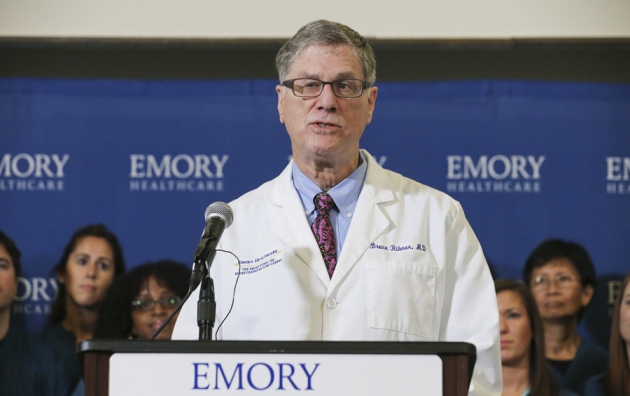

Bruce Ribner, medical director of the hospital’s Infectious Disease Unit, explains how the Americans were cared for and shares lessons that can be applied to help patients in Africa.

Excerpts from his interview with Nature.com

Are Brantly and Writebol now immune to the Zaire strain of Ebola?

In general, patients who have recovered from Ebola virus infection do develop a very robust immunity to the virus. They develop antibodies against the virus and they also develop cell-mediated immunity — the lymphocytes important to form viral control of pathogens. In general, the finding is it’s basically like being immunized — it would be unusual to get infection with the same strain.

Will that immunity afford them protection against other strains of Ebola?

We are still evaluating that in our two patients. Cross-protection is not quite as robust. There are five strains of Ebola viruses. Even though that data is not great, the feeling is there is potential for being infected if you go to a different part of Africa and get exposed to a different strain.

You said “still evaluating.” Are you still caring for Brantly and Writebol?

We are going to be following those two patients as outpatients, and as part of our evaluation they have agreed to undergo additional testing so we can better understand immunity to Ebola virus. We are meeting with them periodically.

What sort of lessons has Emory learned from caring for these two people that would be transferrable to patients in west Africa?

We are not being critical of our colleagues in west Africa. They suffer from a terrible lack of infrastructure and the sort of testing that everyone in our society takes for granted, such as the ability to do a complete blood count — measuring your red blood cells, your white blood cells and your platelets — which is done as part of any standard checkup here. The facility in Liberia where our two patients were didn’t even have this simple thing, which everyone assumes is done as part of your annual physical.

What we found in general is that among our Ebola patients, because of the amount of fluid they lost through diarrhea and vomiting, they had a lot of electrolyte abnormalities. And so replacing that with standard fluids [used in hospital settings] without monitoring will not do a very good job of replacing things like sodium and potassium. In both of our patients we found those levels to be very low. One of the messages we will be sending back to our colleagues is: Even if you don’t have the equipment to measure these levels, do be aware this is occurring when patients are having a lot of body fluid loss.

Our two patients also gained an enormous amount of fluid in their tissues, what we call edema. In Ebola virus disease there is damage to the liver and the liver no longer makes sufficient amount of protein; the proteins in the blood are very low and there is an enormous amount of fluid leakage out into the tissues. So one of the takeaway messages is to pay closer attention to that and perhaps early on try to replace some of these proteins that patients’ livers lack.

Considering how limited resources are in some of these facilities, could health care workers really act on this information?

I think the world is becoming aware that issues like this are not going to go away. The developed countries of the world will have to do our part to assist our colleagues with less-developed infrastructure to care for sick people. I think one of the messages that is going out from many sources is we really have to help countries such as the ones involved in this outbreak to develop their medical infrastructure. Hopefully in five years they will have this infrastructure.

You have said that you are helping to develop new Ebola care guidelines based on your experience. How will those be disseminated?

We have several articles that we have submitted to major medical journals, which are read overseas, where we will be pointing this out. We are working with several government agencies, including the US State Department, to help them come up with lessons learned — guidelines which they will distribute in turn to other countries. It is our goal to help our colleagues overseas.

Alternatively, what lessons did you learn from those health care workers?

Mostly the clinical course of the patients — much like any physician sending a patient to a referral center. They admitted they knew they were kind of flying blind. They’d say, “This is what we observed, but we had no way to test it.”

The World Health Organization [WHO] maintains that patients can continue to be infectious via their sexual fluids for several months after recovery. What did you recommend to Brantly and Writebol?

There are data that go back several decades — over several outbreaks — that suggest when you have individuals that have recovered from Ebola virus infection they may still be shedding nuclear material [genetic material from the virus which could potentially help spread it] in semen in males and vaginal secretions in females — and also, potentially, in urine. People have done this by doing assays looking specifically at the nuclear material of the virus. There has been very little attempt to demonstrate if this is viable virus that these individuals are shedding. It’s important when looking at epidemiological investigations that no one has been able to show people shedding these nuclear materials as a source of infection after they are discharged.

Looking at Ebola survivors who were discharged and successfully resolved the infection, following up several months later and evaluating their family members, there has never been any evidence that family members became infected. A lot of the thinking now is this probably was not live and is not important in terms of control of infection. We did give both of our patients the standard recommendations, which are contained on the CDC [US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] website — not having unprotected sex for three months.

Continue reading @Nature

Leave a Reply